Ink, Pixels, Grit

I didn't find design—design found me. From art school studios to factory meetings, from packaging dielines to cross-continent collaboration, my path has been anything but straight. This is a story about learning by doing, listening through visuals, and designing not just what’s seen—but what’s understood. Here’s how I learned to speak design—in many places, and many forms.

The Web I Weave

A spider spins its web without being asked—it’s just nature. Same with me. I was born to draw—it’s in my instinct.

I entered college as a painting major, drawn to modern art’s bold spontaneity and the tactile appeal of woodwork. Naturally, I gravitated toward installation art, exploring how mediums interact with space, message, and perception. As I built immersive experiences, my focus slowly shifted—from expressing myself to understanding how visuals shape the way people feel and respond. That curiosity eventually pulled me into design. I added it as my third area of study, and something clicked.

↓ Taken in my studio at the end of junior year. I was juggling my major and design courses at the time.

Design, Questioned

My first job was a seasonal designer at a cosmetics company in New York. Later, I found another position in the same town—I was drawn to the beauty industry for its fast pace, trend-driven culture, and exciting projects. I worked on packaging, displays, and catalogs, and eventually began contributing to in-store concepts as well.

One especially cold and difficult December day, I was bitten by a tick and became bedridden for two months. I had no choice but to step away and return home to Virginia. While lying in bed for so long, one question kept returning to me: Why doesn’t good design always lead to better sales? Maybe it’s a common struggle for junior designers, but to me it felt like climbing a mountain—just as I cleared one hill, another appeared in front of me. That very question eventually led me to apply for grad school in 2019. Through branding and UX courses, I found a simple answer: to design well, you must first understand what people want—their desires and their frustrations.

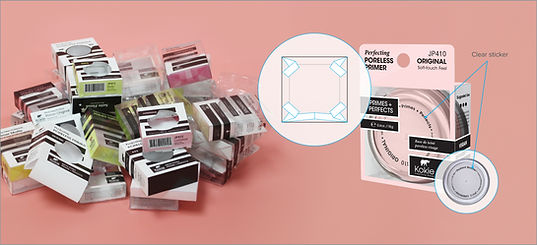

↓ The image below shows some of my work in packaging, display, catalog design, and product photography.

Steps Off the Path

During grad school, I got a call from a Maryland cosmetics company I’d applied to months earlier. A designer had just left; they wanted to interview me. For the next three years, I drove 36 miles each way, spent three and a half days a week in the office, handled the rest remotely—while completing four semesters. Even with nosebleeds in the morning, I never took a sick day. Just once—after catching COVID from the CEO, back from a business trip.

The company involved me in every stage—from lab samples to factory production to vendor coordination—communicating directly as a designer. I also joined development meetings, working hands-on as a hybrid designer-developer.

↓ Most packaging for delicate items uses an inner tray to prevent breakage—but I didn’t want that. The back was crystal-clear and texture mattered, so visibility was key. I dielined it myself—flipping the product so the bottom became the front, then adding a clear sticker with circular text, readable no matter how the product spun. I chose PVC and doubled the dust flaps, folding inward and reinforcing the base—it worked as a cushion.

Bridging Creativity and Business

My next chapter took me into a completely different field—I worked with business professionals and writers. I moved between teams—one morning creating an annual report in Maryland, then switching to a web design with the team in Belgium, or developing infographics alongside writers in London. My role there was that of a visual language interpreter. I wasn’t just designing; I was responsible for ensuring consistency, clarity, and impact across departments.

People described my role in all sorts of ways—“doc-decorator,” “illustrator,” “data visualizer,” even “artist.” People make sense of others through their own lenses, using their own language. It doesn’t matter what I’m called—as long as they pronounce my name right and understand what I do.

↓ This is one example of my work at DAI. The left is what I got from a stakeholder who wanted it polished for external use. The right is what I came up with. Well, the idea was simple: it had to be easy to understand. So I let the visuals do the talking—and moved the full explanation to the next page.

One Out of a Hundred

Design isn’t just about having a vision—it’s about alignment. Even if I’m only responsible for one step out of a hundred, I want mine to be solid. To develop even a one-dollar eyelash glue, there were over a hundred touchpoints: planning, feedback, revision—and then the cycle starts again. No shortcuts. No single loud voice. The team walks the entire path together, and it's not short.

That’s why I don’t normally believe in those “top of the head sparks” people toss out after a meeting. Well—I trust mine, but only when I’ve grounded them. I don’t share until it's ready. If an idea truly feels like gold, you’ve got to dig the mine for it. And I’m always willing to help a teammate dig theirs.

↓ When a team commissions one designer, they often unleash flickering ideas—expecting a polished fusion in return. That was the case here: a group planning a 2022 podcast asked for a logo and graphics. They fired off raw sparks, hoping I’d turn them into something “professional.” But what I took was their intent, grasped was their goal, and shared was direction. I opened up every step without making solo decisions. After the second meeting, the surprise sprinkles stopped. They didn’t mean to interfere—they just hadn’t worked with a designer before.

Designing for What’s Next

In 2024, I was assigned to redesign an internal portal originally launched the year before by another designer. The project had been paused, then revived with a clear directive: reimagine it from scratch—this time, optimized for tablet use. It was a knowledge-sharing dashboard for staff working in remote, low-bandwidth regions. At the time, tablets were the primary tools in the field: portable, durable, and untethered.

But staff began using their personal smartphones instead. Pinch-to-zoom felt intuitive, and batteries lasted longer. Tablets—once essential—quietly faded from daily use. Screen size still mattered, since it was a dashboard with heavy text and wide tables—but it was a UI consideration, not a constraint.

Good UX isn’t just about solving today’s problems. It’s about noticing how people adapt—and designing for what’s next. I now ask not only whether it works today, but whether it will still work tomorrow.